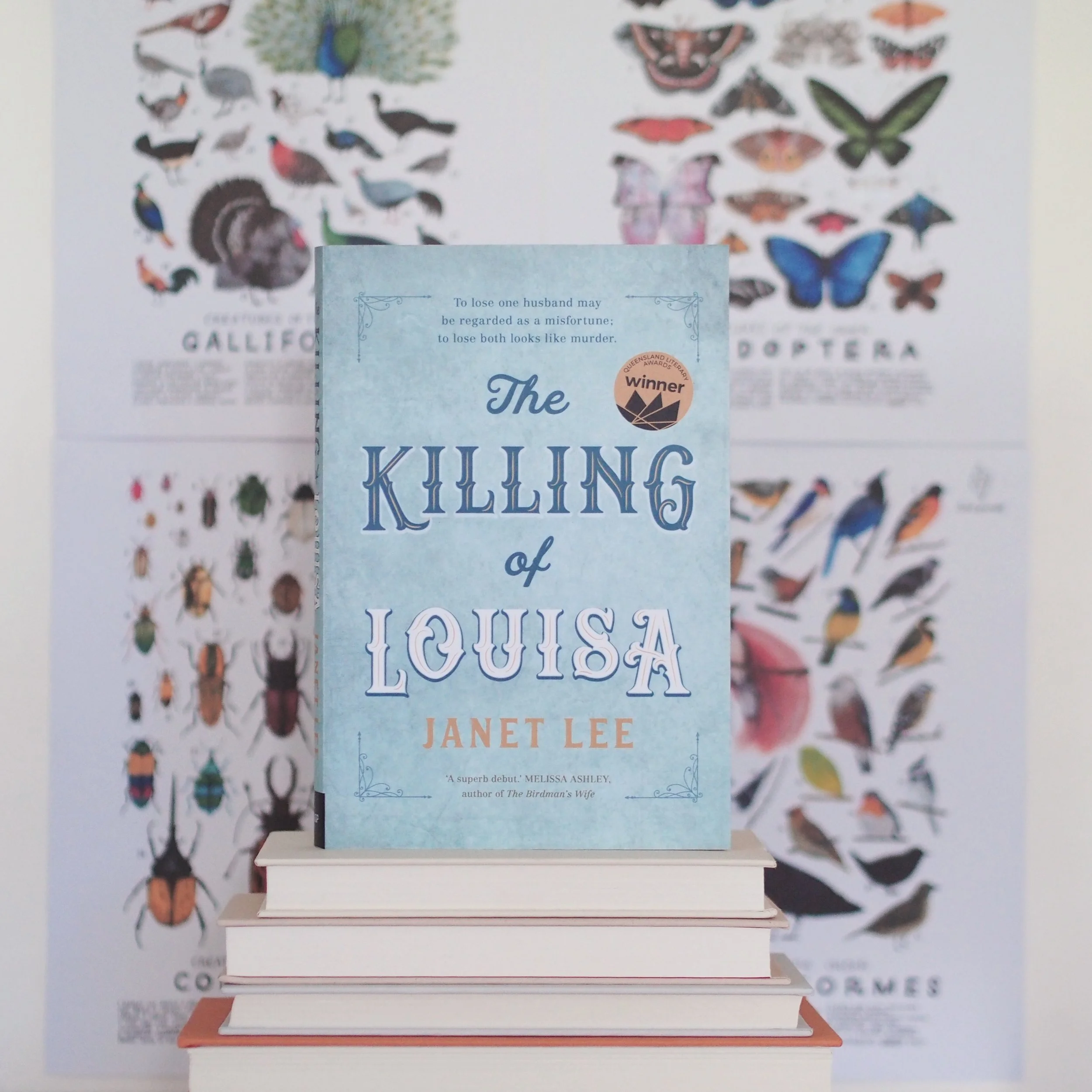

Crime and punishment in Darlinghurst: the last woman hanged in New South Wales.

“If I said things in grief, or if I mourned too little or too much for my husbands, that does not mean that I murdered them, sir.”

By rights, the account of a condemned woman’s last days in a Darlinghurst prison cell shouldn’t be so interesting. After all, isn’t the whole experience of not-knowing-how-it-ends part of a story’s magic?

But readers go into Janet Lee’s The Killing of Louisa with no ambiguity about how this tale will resolve. After all, it’s there in the title, and Louisa Collins is not a figment of the author’s imagination. She was a real woman who was sentenced to hang in New South Wales for the alleged murder of her two husbands. Yet somehow knowing the end of Louisa’s story before it begins does not lessen the impact of the narrative. Instead, the knowledge of Louisa’s eventual hanging hovers forebodingly over the account like a sword of Damocles, serving only to make the story more compelling.

The novel takes place over the six weeks leading up to Louisa’s hanging, a period of time punctuated by uncertainty and confusion. Louisa, who firmly avows her innocence, swings between hope and despair as she reflects on the events that led her to this point. Through Louisa’s memories and the conversations she has with her few allies (a female warder and a minister), readers are invited into Louisa’s past and her person, with all its hardships, flaws and virtues. We are also introduced to the New South Wales of 130 years ago, and it was a special treat for me to read about locations familiar since my childhood.

Above all, though, we are left with an understanding of the utter powerlessness of a woman in 1888 without wealth or title or the protection of a husband to support her in a time of great vulnerability. Louisa’s aloneness is a deep and abiding theme throughout the story, yet she clings to hope and her voice is entirely without bitterness, even when she is forced to process the horrifying grief of her husband and infant son’s bodies being exhumed, or her own daughter giving testimony against her.

Louisa’s voice is matter-of-fact, frank, and does not hold back from detailing both the good and the bad. This, I think, is this brilliant novel’s greatest triumph. There’s such a ring of authenticity to this character that the illusion of historical fiction entirely falls away. The sensation that we are reading Louisa’s own words and thoughts is only deepened by the inclusion of carefully-selected archival material – newspaper articles, telegrams, court reports, and Louisa’s letters. This meticulous research does not detract or distract from the story but, rather, enhances it and proves that truth really can be just as remarkable as fiction.

By the time I had reached the end of the book and read the account of Louisa’s brutal death, I’d come to my own conclusions about her sentence, yet I appreciate that the author pushes the question of Louisa’s guilt or innocence to the background in favour of a much more significant one: was justice served here? If Janet Lee takes a side in this narrative, it is much less about questions of right or wrong and more simply on the side of woman.

Janet Lee

Published September 2018 by UQP Books

Historical fiction, literary fiction, 265 pages