When books are important -and- good.

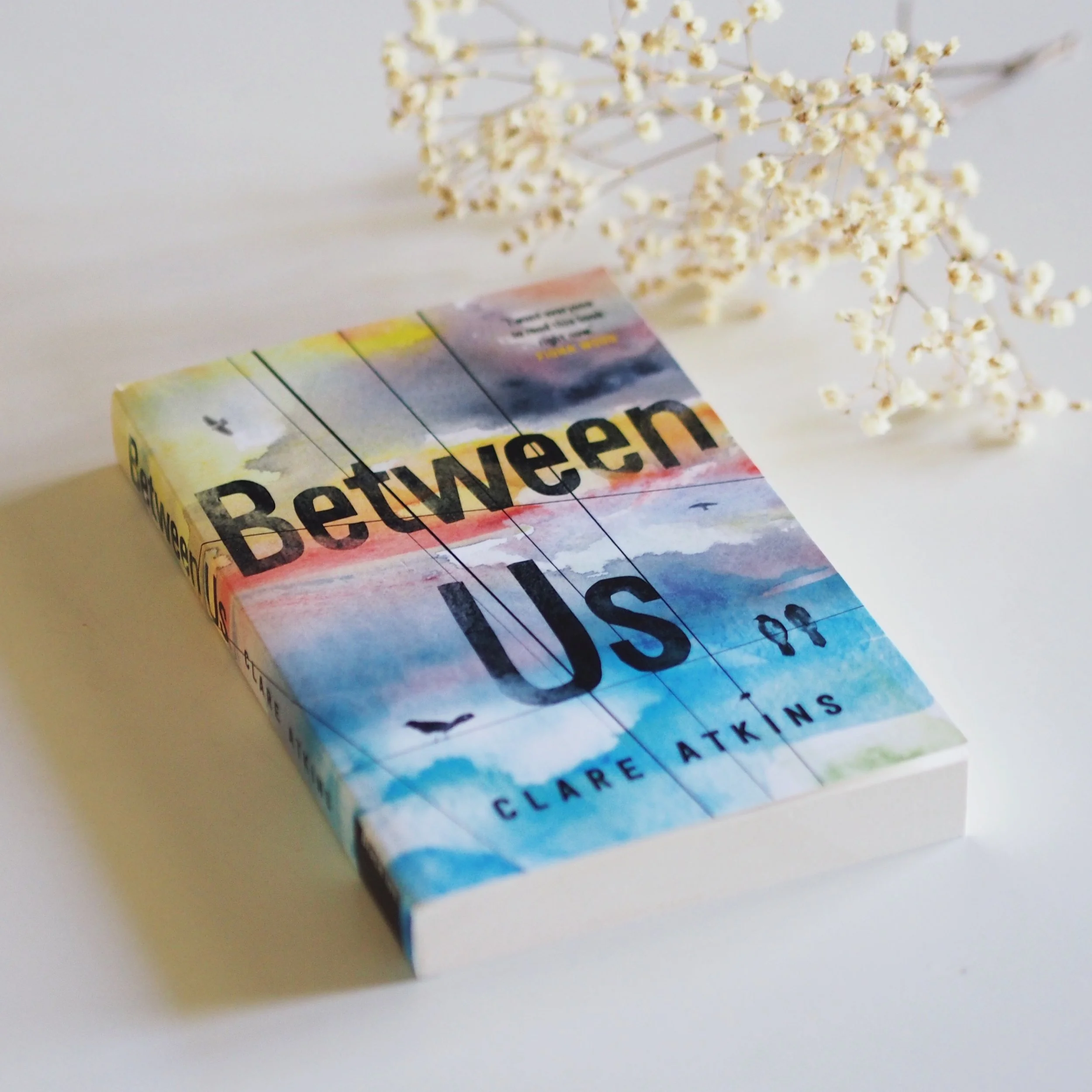

I was at a gathering one Sunday recently, and a couple of different people asked me what I'd been reading lately. (As a side note: people at parties who ask what you've been reading -- who just assume that you will have been reading -- are my kind of people). The book that kept coming to mind was Between Us, a recent YA novel from Clare Atkins, whose 2014 release, Nona & Me, I adored.

Between Us and Nona & Me both deal overtly in what could be described as "issues" -- matters that are part of the current dialogue and seek to address the challenges of society. I have a friend who calls these kinds of books Important Books, and commiserates with me on how they often fall flat, leaning on their own cultural relevance rather than on any story itself.

There is a challenge in writing about issues that are particularly now, issues that -- because of the time and place they inhabit -- speak to a very particular moment in our history. The challenge is twofold: first, making sure it is the characters and not the issue itself that speak the loudest; the second, finding the enduring truth that underlies the temporality of this moment in history.

Between Us is a novel that manages to do both, and in doing so avoids the exploitative nature of the story which says, "Now this topic is Important; how can we make it into a book?" Instead, Between Us responds to the characters who represent the people at the very heart of the issue or moment.

The novel is told in multiple viewpoints and voices as it brings together three key characters: Ana, an Iranian asylum seeker at Wickham Point detention centre in Darwin; Jono, a high schooler roiling in anger after his family's breakdown; and Kenny, Jono's dad, who is determined to do right by his new job at the detention centre.

When Ana is offered day release from the centre to attend school, she meets Jono, and curiosity turns into friendship which turns into something more. But Kenny, already struggling to tie strings with his silent, resentful son, is frightened by Ana's contact with Jono. Other employees at the centre have warned him of the dangers of getting close to any of the detainees, and Kenny can't shrug away his feelings of uncertainty as things seem to be slipping out of his grasp.

The three stories -- Ana, Jono, Kenny -- spiral around one another, exploring each character's past as a reference point for their reactions to the present. The individual voices are finely crafted with an empathetic spirit, avoiding any over-easy characterisation or offering facile solutions. There are no exaggerated "goodies" or "baddies" here. Instead, Atkins shines an honest light on the grief of choicelessness, the ongoing pain of past trauma, the struggle to reconcile broken families, and the tension of belonging to two worlds. In Ana's mother, we see a generous but honest expression of PTSD and post-natal depression; in Jono's father, a softer, milder version of similar pain.

Ana, with her appreciation for "beautiful ugly music" and her fierce love for her family, is both sweet and strong, bruised and bold. Jono is equally complex: intelligent and warm-hearted, but hurt and confused, too, letting himself drift into the seemingly uncomplicated distractions of pot and bad company.

However it's the character of Kenny which surprised me the most, and not just because of the inclusion of an adult (parental, at that) point-of-view in a YA novel, but because his character rings very true. It is here that the nuance of Atkins' writing is most clear. Kenny has a fierce love for Jono and wants to protect him from heartbreak, but he has little knowledge of how to do that. He is sad that Jono has not identified clearly with his Vietnamese heritage, but has no idea of how to foster that identity. Kenny sees his primary role as providing for Jono and taking a hard line when Jono misbehaves, and feels powerless to do any more. He is a man dominated by fear based on the racial stereotypes fed to him by others. Yet he has heart, and a good head on his shoulders, providing a complex and genuine picture of single parenthood.

Together, these ingredients make up a story which manages to be Important only as a byproduct of telling a tale built on compassion, honesty, and strong characterisation. It also seeks to offer hope without the need to tie up every loose end in a happy yellow bow, and puts faces and feelings and connection to a moment in the history of the world (and, particularly, Australia) that is more usually characterised by anonymity and a lack of clear information. I hope, one day, that this book will serve as an account of what once was. For now, however, it marks a picture of what is.

Clare Atkins

Published January 2018 by Black Inc.

304 pages