In the read-up to Sydney Writers' Festival: the best of Australian non fiction

Today, a follow-up to my most recent post, where I shared with you my top fiction pics to read in the approach to Sydney Writers’ Festival. This time, it’s all about the non-fiction: powerful true stories with all the beauty of fiction and the gravitas of fact. Read on for the three non fiction books (two narratives and one anthology) you should check out before the Festival.

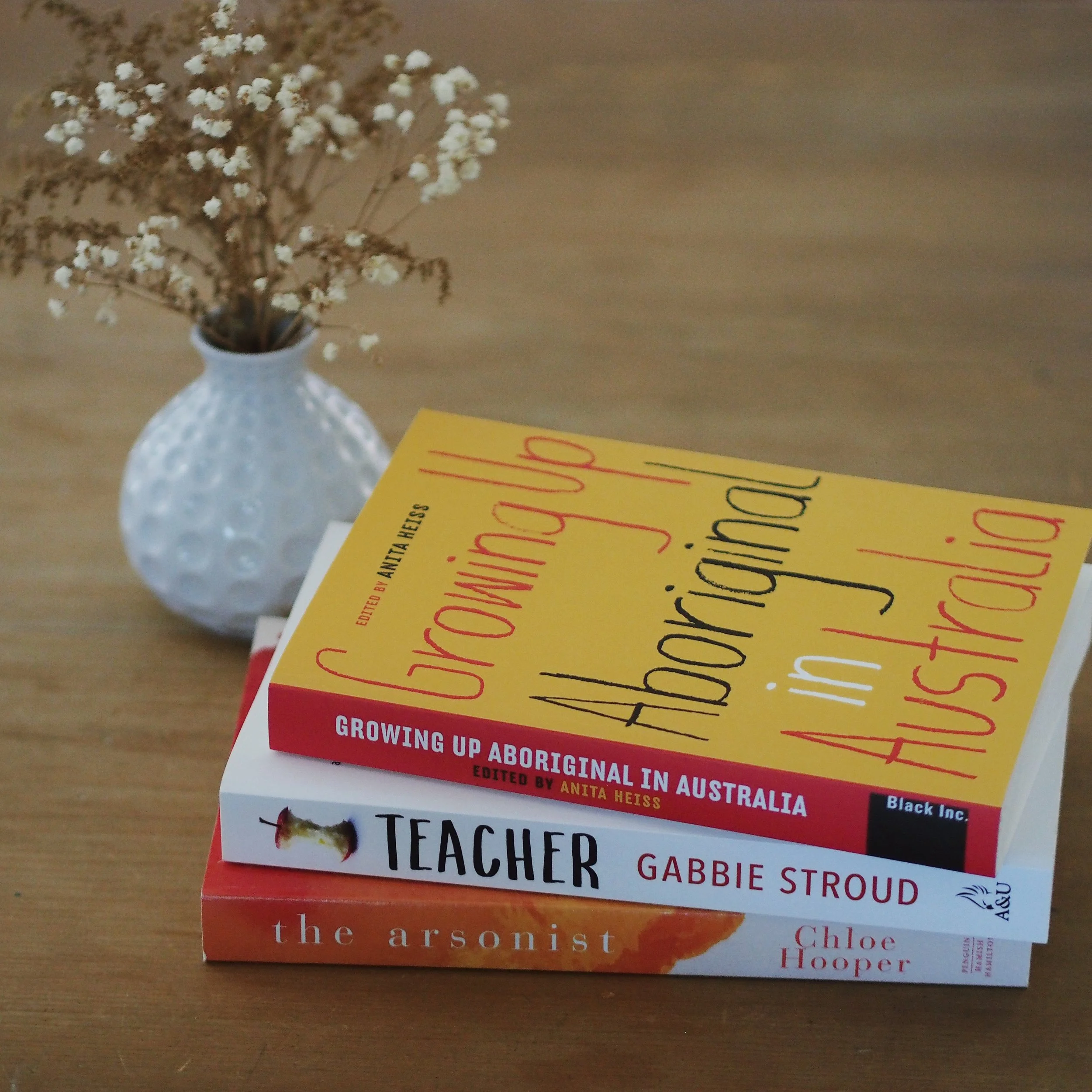

Growing Up Aboriginal in Australia, edited by Anita Heiss

Growing Up Aboriginal in Australia is an anthology collection that engages the mind and the heart with equal energy. Edited by Anita Heiss, the collection contains memoir essays by 52 First Nations people, exploring their identities as indigenous Australians, particularly focussing on their journeys towards adulthood. The authors represented here range from well-known voices (such as Tony Birch, Miranda Tapsell, and Adam Goodes) to emerging writers and activists. The anthology includes works by academics, lawyers, teachers, writers, musicians, professors, artists and more, all of whom come from a diverse variety of backgrounds and experiences.

It would be impossible to summarise each essay, as the stories and their structures are as richly diverse as the authors themselves. The piece from classical opera singer Don Bemrose is in the form of an apology letter to Australia, a satirical repentance for all the ways in which he has failed – or, rather, overturned – society’s expectations and judgements. Writer Tony Birch tells his own story interspersed with original poems, through the narrative of his father’s complex life and relationships. With poetic prose, Evelyn Araluen shares how she and her siblings ‘were taught two worlds pressing in on each other.’ And 13-year-old Taryn Little’s piece is a musing on memories and their role in the formation of her pride in her identity.

These essays revisit childhoods of safety and belonging, as well as those traumatised by separation or abuse. They detail what it’s like to know your tribe and flourish under the embrace of a large family community, as well as what it’s like to grow up without any recognition of your indigeneity. They reinforce the truth that there is no single picture of what growing up Aboriginal in Australia looks like.

Yet one common thread runs through many of these stories: the experience of one’s identity being challenged because one is “too white” or “too black” or simply not whatever the accuser imagined one should be. The misguided and intrinsically racist belief that there is a right way to “be” indigenous is just one reason that we need books like Growing Up Aboriginal in Australia. It’s a rich and important social text that can help shape the future discussion on race and identity and what it means to be Australian (goodness knows it’s a discussion we must keep having). But Growing Up also has value as a beautiful literary text, full of the poignancy of memory and coloured with all the vividness of childhood. It celebrates individual stories, condemns injustice, and honours resilience. Read it to grow, read it to feel, read it to repent, remember, recognise, and respect.

Teacher by Gabbie Stroud

Gabbie Stroud’s Teacher is an engrossing memoir as beautifully-told as any novel. In it, Stroud charts her journey into – and out of – a career in primary school teaching in New South Wales. Her story explores her hopes and aspirations as a child, the first stirrings of inspiration as a hopeful young writer, and the influential teachers who imparted wisdom, passion, and heart into their work. The memoir moves onto Stroud’s tertiary education, and the teaching degree which is a perfect fit for her natural intelligence, personal interests, and nurturing nature. Stroud writes of the bright-eyed hopes and ambitions fostered at university, when everything seems clear-cut and full of creative possibility.

But her first teaching post is a startling call to reality. It quickly becomes clear to Stroud that intellect, training, and compassion are not enough. As she teaches in private and public schools both in Australia and overseas, she wrestles to meet the needs of kids who are in and out of foster care, those dealing with complex trauma, kids who have specific learning needs, and others who are struggling and hurting. Caring for vulnerable children, making sure they are physically and emotionally safe, and meeting them right where their challenges are could be a full-time job in and of itself; Stroud tells of teachers who teach in darkened classrooms so as not to stress those with sensory issues, or those who bring groceries and scour the lost property basket for the kids who turn up to school unwashed and unfed. Yet at the same time, Stroud and other gifted teachers like her must also ensure that all children, the ones with natural aptitude as well as those with complex challenges, are learning to love learning and progressing in the skills which they’ll require to be competent, creative, functional members of the community.

This tension between the practical and relational aspects of the work is depicted with warmth and feeling – and, at times, sorrow. Stroud speaks with gratitude of the mentors whose work is so influential to her own, people who love children, love education, and generously share of their own wisdom and practice. Almost universally, these teachers understand that the role of an educator does not end at 3.30pm as the last bus leaves the school lot. There is the ongoing responsibility of curriculum planning and development, marking and preparation, all of which has teachers working long after-school hours and putting in time on the weekends. But then comes the advent of standardised testing and increased pressure on teachers to reach a universal standard of achievement that can be quantified, reported, and published. Stroud watches as the heart and soul are yanked right out of teaching and the new expectation is an unattainable dream that leaves teachers mentally, emotionally, and spiritually depleted.

At this point, Stroud’s narrative becomes truly gut-wrenching. A deep sense of grief pervades the story and the anxiety is palpable, contagious. Going into this book, I expected an intelligent critique of the education system as it stands in Australia, but it proved to be both less and more than that. It’s one woman’s grief over the impossibilities of working with broken kids in a flawed system. This is not a rage piece or an indictment against the role of teachers. Rather, it’s a lament for all that teaching strives to be and cannot. It’s a sense of despair over the kids who slip through the cracks because education is a holistic work, not a job that must be meted out by a trained professional only between the hours of 9 and 3. It’s a deep sorrow for how teaching meets some of these kids’ needs but never all of them, and the acknowledgement that, for some kids, school is the only security they’ll get. And it’s a depiction of pure exhaustion, an honest and non-didactic reminder that teaching isn’t all bubble painting and shiny red apples.

This is one for the teachers who own their jobs with passion but sometimes feel a deep bone weariness and a sense of despair at the impossibilities of the work. It’s one for leaders in the education field who can effect change at the ground level. And it’s one for those who care about our children and the world we are helping them to make.

The Arsonist by Chloe Hooper

In a year already filled with excellent non-fiction reads, Chloe Hooper’s The Arsonist stands out with particular brilliance. I was prepared to love it, having been mesmerised by The Tall Man some years ago, but Hooper works with tricky material; how compelling can a thorough investigation of an arson case be? I shouldn’t have doubted. In Hooper’s masterful hands, a deeply-researched reconstruction of the 2009 Black Saturday fires in the Latrobe Valley proves to be incredibly compelling.

Reading with the pacing and urgency of a thriller, The Arsonist is a true crime drama in three acts. The first feels like a police ridealong. We are swept into the early days of investigation after the fires, while the earth still sweats ash and a town is mourning its many dead and injured. In a manner both intimate and visceral, Hooper depicts the impossible power of fire and humanity’s uneasy and occasionally fetishized relationship with its untameable might. Hooper’s research, the beating heart of the book, never feels superfluous or there simply for its own sake. Instead, it makes the realities of the Black Saturday fires terrifyingly tangible. The narrative is gut-wrenching and emotive, but never overwritten. If anything, Hooper underplays the drama, letting the events unfold in the survivors’ own words, as vivid as any work of fiction.

The second act follows the lawyers on both sides of the court as they attempt to make a case for and against the man charged with lighting the fires. This section builds a fascinating picture of the demography of an arsonist and makes real the challenge of law enforcement and defenders who are charged with piecing together a puzzle with an abundance of missing parts. The frustration of the interview process, of working with a defendant who is either incredibly mentally and socially challenged or just incredibly crafty, is palpable, as is the challenge of pursuing justice in an area of Australia with a higher proportion of vulnerable or needy people.

The third act, The Courtroom, dives deep into the arsonist’s trial, revisiting with feverish intensity the experiences and perspectives of key witnesses and victims of the fires. It zooms in on the arsonist himself, considering the pathology of a criminal who perhaps doesn’t understand the weight of his own crime, and the lack of special care afforded to those who don’t naturally conform to the standard boundaries of society. It looks, too, at the aftermath of a tragedy that changed the shape of a community and will be remembered in history as one of Australia’s greatest disasters.

Throughout the book, Hooper maintains a level of journalistic integrity that is remarkable for its measured consideration coupled with a keen interest. It’s a story that is both sweeping and personal, deeply reminiscent of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, and just like Capote’s true crime narrative, this one will remain chillingly pertinent for years to come.

Sydney Writer’s Festival runs from the 29th of April to the 5th of May this year. Check out the program for full details of events and interviews or jump straight to sessions with Evelyn Araluen, Gabbie Stroud, and Chloe Hooper.